Shakespeare and the Common Core

Across the United States, education is undergoing a sea-change (into something rich and strange) surrounding the adoption of something called the Common Core State Standards.

Standards are simply a list of what students should be able to do by the end of each grade. Traditionally, these have been defined by states, with a requirement for them to do so by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. States still define their own standards, but, in an unprecedented act of coordination, 45 states (plus the District of Columbia and a few of the territories) have adopted the Common Core as their state standards. Full adoption has been targeted for next year, though New York has started phasing in significant portions of it this year.

Love it or hate it, the Common Core represents a new direction in pedagogical thinking, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Personally, I think the Common Core standards are a lot better than the existing New York State Standards, but we’re going to have to suffer through a difficult transition period before we can reap the benefits of that improvement. Right now is probably the most difficult time, as we have to deal with students who are not starting on what the new structure defines as grade-level, a lack of Common Core-aligned teaching materials, and uncertainty surrounding precisely how these new standards will be assessed. May you live in interesting times.

As with anything new and complex, there are going to be a number of misconceptions floating around about it. One of the most prevalent I’ve seen is that the Common Core eliminates (or at least de-emphasizes) literature, in favor of informational texts. In particular, many are convinced that Shakespeare will be replaced entirely by non-fiction, as public education descends into a Dickensian nightmare of Shakespeare-deprived conformity and standardization.

In fact, Shakespeare is mandated by the Common Core.

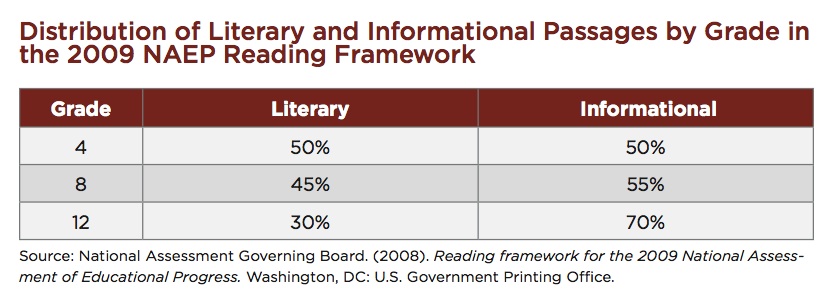

The confusion seems to stem from a chart that appears on page 5 of the English Language Arts Standards document, outlining the percentages of literary vs. informational texts included in the National Assessment of Educational Progress:

(Click for a larger image.)

The Common Core is explicit about aligning curricula with this framework, but it is just as explicit about how that alignment should be distributed:

Fulfilling the Standards for 6–12 ELA requires much greater attention to a specific category of informational text—literary nonfiction—than has been traditional. Because the ELA classroom must focus on literature (stories, drama, and poetry) as well as literary nonfiction, a great deal of informational reading in grades 6–12 must take place in other classes if the NAEP assessment framework is to be matched instructionally.

So, despite the canard that high-school English classes will only be allowed to teach literature 30% of the time, the 70% informational text requirement refers to the entirety of student reading across the curriculum. Given that one of the major shifts is an increase in reading and writing in the content areas, the ratio makes sense.

Let’s say that, over the course of a particular unit, a high-school English teacher is assigning 3 literary texts and 1 informational text. That means that (text length aside) students are reading 75% literature in English class. And if this is the only reading the students are doing, then they are reading 75% literature overall. But now imagine that, during the same timeframe, they are also reading 2 informational texts in social studies, 2 informational texts in science, and 2 informational texts in all of their other classes combined. They are still reading 75% literature in English class, but this now represents 30% of their reading overall.

And, far from being lost in the informational-text shuffle, Shakespeare now becomes the man of the hour. As the only author explicitly required by the Common Core, Shakespeare must be taught in grades 11 and 12 (see page 38, right column, Standards 4 and 7). Shakespeare is also included in the recommended texts for grades 9 and 10 (see page 58, left column, center). And Shakespeare is not excluded for younger students either, as the standards outline only the minimum of what must be taught in each grade. The Common Core does stress using authentic texts, so updated language versions of Shakespeare would be frowned upon, but that’s actually an adjustment I can get behind.

There is a lot of controversy surrounding the Common Core, and a lot of objections surrounding the new changes. Some of these objections are legitimate, and some are not. I look forward to continuing that conversation as the implementation develops. But rest assured that Shakespeare isn’t going anywhere.

January 8th, 2013 at 9:11 pm

[…] « Shakespeare and the Common Core […]

October 2nd, 2013 at 7:03 pm

[…] I thought I’d take this opportunity, while the federal government is shut down over the question of its own power to legislate, to talk about another somewhat controversial initiative, namely the Common Core State Standards. […]

December 31st, 2013 at 7:49 pm

[…] Shakespeare and the Common Core (January […]

February 3rd, 2014 at 10:28 am

You raise a really great point about the ratio between literary texts and informational texts. I agree that many teachers are misinformed about this ratio and believe that the ratio includes ELA texts only. In reality, the ratio is across all of the content areas. As you mentioned, it does not take away a great deal of literature from ELA.

I, too, am thankful that the Common Core standards mandate teaching Shakespeare. I actually just completed the Grade 9 Romeo and Juliet module with my students. There were some very helpful discussion questions in the module and it did a great job of interweaving Shakespeare’s text with Baz Luhrmann’s film version.

Although the module began with the play’s prologue and ended with the very last line of the play, students did not read the entire text. Instead, students read only part of Shakespeare’s text and filled in the gaps with the film version. This was an interesting approach to Shakespeare. I’m not sure how I feel about eliminating entire scenes of Shakespeare’s text, but it seemed to work for my 9th grades that have not had a great deal of experience with Shakespeare.

February 7th, 2014 at 11:00 pm

Welcome, Victoria!

I don’t have a problem with students reading part of a play, and filling in missing scenes using a movie is a great solution for making it work.

The Baz Luhrmann version is highly engaging, and in the original language, so I think it’s the perfect choice!

June 27th, 2015 at 7:05 pm

ally, really, really, really need to start teaching literary theory in high school. So many people don’t understand the poetry and depth of Shakespeare and they blame the language, or other visible phenomena. In reality, you don’t understand Shakespeare because poetics is an acquired concept, largely incompatible with the science-worshipping modern era. In reality, the world is not quite so simple as it seems and Shakespeare is a good way for teacher to introduce the concept. If you’re a teacher who has no clue how to teach Shakespeare, acquire Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare and the Invention of the human and make it your literary midrash. Remember, you are teaching the writings of what some consider to be a secular diety and you should treat it as such. You should also do research into different interpretations of Shakespeare through the ages and you should take a stance yourself! First and foremost you are a guide but you should pick a literary criticism movement you agree with and make that your stance. As every good essayist knows, a person with a bias is far more interesting than one without. Remember, you are a teacher, not a textbook. Try to make Shakespeare come alive for every student who wishes to partake.

July 8th, 2015 at 6:59 pm

Literary criticism in high school? I’d have to dissent on that one. Even honors students must work hard to give a sound reading of the primary text and be able to set forth the elements of plot and character. Teachers should aim principally at encouraging and assisting learners in mastering the basics. Additionally, few things are as educational as memorization of the sonnets and great soliloquies, and acting out scenes and skits is great fun. All that is appropriate for the secondary school environment. It is a direct encounter with the text. That fresh and invigorating encounter is not facilitated by the importing of theory of any kind. On the contrary. To paste ideological spectacles over the eyes of students and demand that they read Shakespeare in light of this or that doctrine, no matter how pervasive, is to interfere with the natural assimilation of the text and to teach students precisely how not to read. Theory has a place in 600 level university courses and higher, where very advanced students are made aware of various textual aporia which can be addressed in terms of philosophy. That is a valid exercise, but suffers from the drawback of making of each and every reader a committed ideologue who can barely tolerate a rival or alternative paradigm. At lower levels it represents instruction in prejudice and presumes that students have already mastered fundamental literary skills, a dangerous assumption these days. Whoever imagined that the introduction of theory made reading of challenging texts easier? With all due respect, that is to march in precisely the wrong direction. Reading Shakespeare is a deeply personal business and students need to be helped to hear the poet’s voice in relation to themselves, their lives and history without the interference presented by doctrine. I have personally seen the confusion such mistaken pedagogy brings about. Students who cannot explain Bassanio’s relationship to Portia and Antonio are asked to explain what Karl Marx would think about usury in the 15th century and how that impacts the view of the play today among critics at Oxford and Yale. That way badness lies. For those wishing to see this argument developed in detail over the range of Shakespeare’s art, please see Hamlet Made Simple and Unreading Shakespeare in Amazon Books.

July 24th, 2015 at 7:25 pm

I deplore the practice of not reading a complete text. BOO to any teacher who thinks it is ok to supplement big chunks of the play with a movie. You are an embarrassment.

July 25th, 2015 at 6:08 am

Linda, thank you for taking the time to visit and comment. But name-calling aside, I’d love to hear the reasoning behind your admonition.

When teachers plan, they need to take a number of factors into account, e.g., what they want their students to learn by reading Shakespeare, student age and preparedness, time allotted, etc. Reading part of a play instead of a whole play might better fit a teacher’s specific situation.

Some teachers don’t teach Shakespeare at all. Others teach using an updated modern-language version. I assume you’d agree that having students read part of a text is superior to those practices. I want students to read Shakespeare in the original language. I want them to speak the text out loud. I want them to do something creative with it. What if I don’t have time to do that and read the entire text? Which should I choose?

And, in fact, outside of my graduate courses, I have rarely asked students to read every word of a Shakespeare play. If we’re performing it (and we probably are), I’ll have edited it for length. If we’re not, I may skip over a few of the less consequential scenes to spend more time digging deeper into the good stuff.

Note that I mostly work with middle-school students, and don’t have a problem with a high school class reading an entire text. Some teachers even have the students themselves edit the text for production. I just don’t agree with the blanket statement that all students must read every word of the text in every situation, just so the teacher can feel good about being a purist.

If you have an argument to the contrary, I’d be interested to hear it. I always find these kinds of conversations to be valuable to my developing philosophy. Welcome to you, and to Adam and David who have opened up an interesting conversation as well. I had meant to respond to Adam, but David hit a lot of the points I was going to make. But I thank you all for helping the conversation to continue.

August 17th, 2015 at 10:43 am

Thanks, Bill. I teach Shakespeare to English learners in China and do so with a measure of success. I supplement an encounter with the text with a film version including subtitles about a third of the way into the semester. My students love Julius Caesar and King Henry IV (and my lectures on these plays). My undergraduates here enjoy the challenge of reciting the “I know you all” soliloquy in H4 and Sonnet 18. We learn much about English and something about life. I do also share with my grad students some ideas in the books I mentioned, Hamlet Made Simple and Unreading Shakespeare. They appreciate my comments on the risks of theory as a pedagogical instrument.