I thought I’d take this opportunity, while the federal government is shut down over the question of its own power to legislate, to talk about another somewhat controversial initiative, namely the Common Core State Standards.

It should be noted that this is not a simple left-right issue. At a recent conference, I heard Kim Marshall joke that he never thought he’d see national standards because “the right doesn’t like national, and the left doesn’t like standards.” So, as you might expect, the Common Core seems to be embraced by moderates in both parties, while being attacked by extremists on both sides. Teachers and parents, who are the most directly affected by the changes, express the same range of opinions as policymakers and pundits. So, the discussion continues.

To get a sense of the issues involved, as well as the general tone, check out this New York Times editorial by Bill Keller, and this response by Susan Ohanian.

For the record, I agree with the Bill Keller editorial (you can just change that “K” into an “H” and we’re good). I’m a fan of the Common Core, though I have a number of concerns about the way it’s being implemented. But I respect the opinions of many who oppose it, and understand the quite valid reasons why they do. Unfortunately, most of the rhetoric that I encounter against the initiative is either focused on areas that have very little to do with the standards themselves, or are based in a fog of misinformation.

Now, if you’ve read the standards, and you honestly believe that we should not want our students to be able to cite evidence from informational texts to support an argument, I’m very willing to have that conversation. If you think the Common Core shifts aren’t the right direction for our students, I’m very willing to have that conversation. If you have a problem with emphasizing literacy in the content areas, I’m very willing to have that conversation. That’s just not the conversation I’ve been hearing about the Common Core, and if we’re going to discuss these very large-scale changes in the way they deserve to be discussed, we need to clear the air of distractions and distortions.

With that in mind, I present the Top Ten Most Common Objections to the Common Core, and my responses to them. This is meant to be the beginning of a conversation and not the last word, so please feel free to continue the discussion in the comments section below.

1. The Common Core is too rigorous. The standards are not developmentally appropriate.

I think we’re feeling that now because we’re transitioning into these standards from a less rigorous system. If students come in on grade level, what they’re being asked to learn in each year is very reasonable. The problem is that we’re so far from that “if,” that the standards can often seem very unreasonable. Add to that a rushed implementation, complete with career-destroying and school-closing accountability, and the Common Core expectations can leave a very bad taste in our mouths.

What’s more, the Common Core includes qualitative shifts as well as quantitative shifts, so students will be as unfamiliar with the new ways of learning as their teachers are. The good news is that each year we implement the Common Core, students will become more used to Common Core ideas such as text-based answers and standards of mathematical practice, and will be better prepared for the work of their grade each year. It will likely get worse before it gets better, but I do think there is a light at the end of the tunnel, and it will at least become visible in the next year or two.

2. The Common Core is not rigorous enough. My state had better standards before.

Well, the standards are meant to represent only the minimum of where students need to be in their grade level in order to be on track for college and career readiness by the end of Grade 12. So if you can meet these standards and then exceed them, more power to you. States that adopt the Common Core are also free to change up to 15%, and to add additional standards as well.

So here in New York State, we added Pre-K standards that aren’t in the national version, we put in additional standards throughout the documents (including Responding to Literature standards in ELA and teaching money in early-grade math classrooms), and we still retain the state-wide content standards in social studies and science that students need to pass their Regents. And even where states are slacking, a high-performing school won’t suddenly lower their standards just because they can. That’s not how they became high-performing schools in the first place.

3. The Common Core is a mandated top-down program that infringes on state control of schools.

The Common Core is not mandated by the federal government. States can choose to adopt the Common Core or opt out. I hesitate to present the most blindingly obvious of proofs, but here we go: not all of the states adopted the standards. Some states chose to opt out. That should suffice as proof enough that states can choose to opt out if they want to.

Did the federal government sweeten the deal by adding Race to the Top incentives for states that adopted the Common Core? Yes. But that’s bribery, not coersion. You can say no to a bribe, even if you need the money. And this wasn’t even that much of a bribe, as everyone knew there were only going to be a limited number of states that won Race to the Top funding and Common Core adoption was far from a guarantee.

Whether you love or hate the Common Core, it was your state legislature that adopted the standards, and the credit or blame should be placed there. States are just as capable of having cynical self-serving politicians as the federal government is, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. But some states may have genuinely adopted the Common Core to improve education for their students, even if you don’t think it will.

Frankly, I’m no more a fan of Race to the Top than I was of No Child Left Behind. I don’t think states should have to compete for education funding. And there were other incentives in the Race to the Top formula I had issues with, like the charter school expansions. But these are criticisms of federal education policy, and not the Common Core standards themselves.

4. The Common Core is a result of the corporate reform movement that’s undermining public education.

Maybe.

I don’t think the standards do undermine public education, though, and I believe the people who actually put them together are earnest in their attempts to improve it. I’m not blind to some of the strange bedfellows involved with the process, but if an idea leads to good things, I don’t care where it comes from. This is an argument that just doesn’t work on its own. Just because Bill Gates funded it, it isn’t necessarily Windows 7. Zing!

5. The Common Core is only about testing and accountability.

I hate to break it to you, but the testing and accountability movement has been around a lot longer than the Common Core. We’re already teaching to the test, so it makes sense to design a better test, one worth teaching to. You can read about early attempts to align New York’s state-wide exams to the Common Core in this article, and I’m quoted towards the end, but the bottom line is that they didn’t go very well.

Two multi-state consortiums are now hard at work to build a better test, though this turns out to be a tougher job than they originally thought. They are talking about having students take the state-wide (actually, consortium-wide) tests on computers, which means that every school needs to have computers. That could be a logistical nightmare in itself, but it could also mean more funding for computers in schools.

In New York City, teachers are being evaluated through a system that uses test scores, in one form or another, as 40% of a teacher’s score, while the other 60% will be based on the Danielson Framework. In my opinion, that’s a vast improvement over using test scores alone, which even the Gates-funded MET study doesn’t endorse.

6. The Common Core is a conspiracy to keep the poor uneducated.

No, that’s what we have now. There is a strong correlation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Having a set of common standards is one step in the process of attempting to close that gap.

7. The Common Core replaces literature with government manuals.

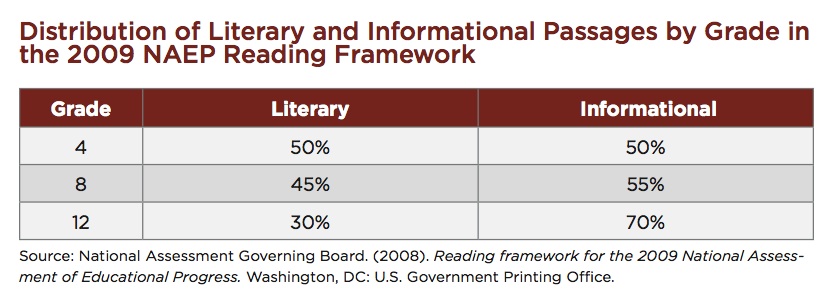

That simply isn’t true. There is an entire section of the standards that covers Reading Literature. There may be a government manual listed somewhere in the examples of informational texts, but it’s disingenuous to hold that up as the centerpiece of Common Core expectations for student reading. Anyone who makes this argument is either unfamiliar with the standards, or uninterested in engaging in a serious discussion about them.

8. People are making money from the Common Core!

This is true, in as much as we need people to write tests, publish classroom materials, and train teachers. But we would have needed this anyway, Common Core or no.

Liberals tend to think that everyone should do their jobs with the purest of motives, and if someone’s profiting from something, it must be an evil conspiracy. Conservatives tend to believe the opposite: that if you made money from an idea, then that proves the idea had market value, and those who improve the system deserve to profit from their innovations. I take a more neutral view of profit’s correlation with good in the world. I work in teacher training, and the Common Core affects what I teach, but not how often I teach or how much money I make. I have no financial interest in defending the Common Core.

Keller’s editorial estimates the costs of the new tests at about $29 per student, in a system that spends over $9,000 per student in a year. You might not like the Common Core for other reasons, but cost alone can’t be the only reason to oppose it.

9. These Common Core-aligned materials I have are bad.

I don’t doubt it. But just because a product claims to be “Common Core-aligned,” it doesn’t mean that it is Common Core-endorsed. I have no end of problems with the range of “Common Core-aligned” curricula being rolled out by New York City alone. This is not a function of poor standards, but rather poor implementation.

By the way, a lot of the Common Core-aligned materials were delayed getting into schools this year, even as teachers were required to start using them. You don’t have to convince me that we’re having implementation problems.

And I spent last summer modifying my own organization’s social studies curricula to be Common Core-aligned, and I feel strongly that our products improved immensely because of it.

10. The Common Core is untested, and shouldn’t be implemented on such a large scale without a pilot program.

This is from Reign of Error author Diane Ravitch, and she makes a fair point. But nothing’s written in stone. The standards will work in some ways and need mending in others. And where they need mending, we’ll mend them. Ten years from now, we may come to see the current version of the Common Core as a really good first draft. Or we may remember it as New Coke. There’s no way to know until we try it out. That can be used as an argument for it as well as against it.

I do think that we should do everything we can do to make it work. That’s the only way we’ll really know if it doesn’t.

Honorable Mention: President Obama is for it, and therefore I must be against it.

Hey, look! Someone over there is getting health care.

I really do see a lot of parallel between the Affordable Care Act debacle and the Common Core controversy. Tea party Republicans want to talk about how Obamacare will destroy the economy and force the government between you and your doctor and lead to the apocalypse, but they really oppose it on ideological principles. If they would talk about their principles, we could have an honest debate, but they know these principles sound cold and selfish, so they obfuscate. Common Core opponents dance around the actual changes being made in education because most of them make sense. The real concern, as I see it, is the danger of the larger corporate-funded movement to use testing and data to prove the ineffectiveness of public education in order to move to a privatized free-market system.

That’s a concern worth discussing directly, and I’m very willing to have that conversation.